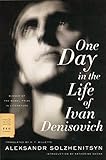

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's short novel of a day in a Stalinist camp is a story of human dignity, survival and faith. The Stalinist prisons were not for criminals, and they attempted to break the wills of those in the camps. Ivan, or Shukhov as he is referred mostly in novel, is essentially a dignified and proud character. The characterization is subtle. He is from a peasant background and not particularly intellectual, religious, or rebellious, but there is a quiet dignity and pride about him. He is simple, and very much the beautiful every man:

Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn's short novel of a day in a Stalinist camp is a story of human dignity, survival and faith. The Stalinist prisons were not for criminals, and they attempted to break the wills of those in the camps. Ivan, or Shukhov as he is referred mostly in novel, is essentially a dignified and proud character. The characterization is subtle. He is from a peasant background and not particularly intellectual, religious, or rebellious, but there is a quiet dignity and pride about him. He is simple, and very much the beautiful every man: And although he had strictly forbidden his wife to send anything even at Easter, and never went to look at the list on the post--except for some rich workmate--he sometimes found himself expecting somebody to come running and say: 'Why don't you go and get it, Shukhov? There's a parcel for you.' Nobody came running. As time went by, he had less and less to remind him of the village of Temgenyovo and his cottage home. Life in the camp kept him on the go from getting-up time to lights out. No time for brooding in the past.I liked this novel. I think it's hard to pinpoint what's particularly unique or special, but it is a straightforward and well told story. There seems to be such wonderful simplicity in the prose that gets across the character and the experience of camp life so well:

Shukhov's idea of a happy evening was when they got back to the hut and didn't find the mattresses turned upside down after a daytime search.The book ends with a discussion of faith, religion and spirituality which is part of the survival of the camp. In his own way, Shukhov is spiritual in his actions and the way he carries himself. He has hope after all:

For a little while Shukhov forgot all his grievances, forgot that his sentence was long, that the day was long, that once again there would be no Sunday. For the moment he had only one thought: We shall survive. We shall survive it all. God willing, we'll see the end of it.

From my blog Aquatique.

This would be my first book of the 5 book challenge.

1 comment

I read it a few months back. Eerily reminiscent of lost times and ways - both fortunate and (mostly) unfortunate. Shall give my version of it soon.

Post a Comment